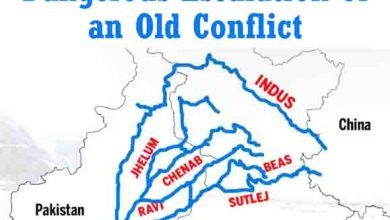

Urgent Reforms Needed: Pakistan Pushes for New Protocol to the Indus Waters Treaty

Pakistan advocates a Protocol to the Indus Waters Treaty to address climate change, upstream dam abuse, and trilateral cooperation with China.

The Protocol to the Indus Waters Treaty is no longer a theoretical concept — it is becoming an urgent diplomatic necessity. Signed in 1960 with the support of the World Bank, the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) has largely maintained peace between India and Pakistan over water rights for 65 years. However, changing geopolitical tensions and climate instability have put the treaty under immense pressure.

As Pakistan sees it, any renegotiation must protect its vital interests as a lower riparian state, particularly as India issued formal notices in 2023 and 2024 to open discussions for modifying the treaty under Article XII.

India’s Notice and Pakistan’s Response

Under Article XII of the IWT, any changes must be ratified by both governments. In 2023 and 2024, India issued two notices to Pakistan seeking to renegotiate the treaty. After India put the IWT in abeyance in April 2025, Pakistan recently invited India to reopen talks, signaling a willingness to engage, but with firm conditions.

Any Protocol to the Indus Waters Treaty must address longstanding Pakistani concerns — particularly India’s unilateral dam constructions, climate change vulnerabilities, and the absence of multilateral frameworks.

Why a Protocol to the Indus Waters Treaty Is Necessary

While the IWT has successfully regulated the distribution of the Indus basin rivers, it no longer addresses 21st-century challenges. Four critical areas require urgent inclusion in any future protocol:

1. Trilateral Inclusion of China in the Protocol

Pakistan proposes expanding the IWT into a multilateral treaty that includes China. This may seem ambitious, but there is legal and strategic precedent:

- The Mekong River Commission includes all riparian states in Southeast Asia.

- The Nile River Basin Initiative and Danube Convention demonstrate that regional cooperation over shared rivers is possible and effective.

- The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Charter, under Article 3, calls for cooperation on water and environmental management. India, Pakistan, and China are all SCO members.

Since the Indus River originates in Tibet, involving China could lead to a more holistic and peaceful water-sharing framework. Notably, India’s own decision to revoke Article 370 in August 2019 inadvertently gave China a legal locus standi by altering the status of disputed territories.

2. Judicial Oversight of Dam Construction by India

At present, India can decide to build dams on western rivers based solely on its internal needs, bypassing meaningful consultation. Under Annexure D (Clause 8 and 9) of the treaty, Pakistan can only challenge technical design parameters, not the strategic decision to build a dam.

To counter this imbalance, the Protocol should propose:

- Three-year prior notice for any dam project.

- A judicial mechanism through the International Court of Justice (ICJ) or an independent Court of Arbitration to adjudicate on dam necessity, design, and potential harm.

Such safeguards would prevent India’s unilateral water grabs and protect the ecological and agricultural lifelines of millions in Pakistan.

3. Addressing Climate Change in Water Management

The 1960 IWT was built on the assumption of predictable hydrology. But the climate crisis has rendered these assumptions obsolete:

- Glacial melt is accelerating in the Himalayas.

- Monsoon patterns have become erratic.

- Flash floods and extended droughts now regularly disrupt flow patterns.

The Protocol should introduce:

- A Permanent Panel of Climate Experts from all parties.

- Joint data collection systems for rainfall, snowpack, and glacier mass balance.

- Real-time hydrological monitoring to inform seasonal water allocations.

Climate resilience must be embedded in the future architecture of the Indus Waters Treaty.

4. Ensuring Minimum Flow for Downstream Survival

International law mandates minimum flow requirements for downstream states to ensure ecological integrity and human survival. However, the current IWT lacks such a provision for eastern rivers.

India, as the upper riparian, currently exercises near-total control, often releasing water arbitrarily or not at all. This affects biodiversity, farming, and drinking water access in Punjab and Sindh.

The new Protocol must enshrine:

- A minimum environmental flow commitment.

- Transparent and verifiable flow metrics.

- Penalties for non-compliance.

This would align the IWT with international norms set by the UN Watercourses Convention and the Berlin Rules on Water Resources.

Conclusion: A Time for Bold Diplomacy

The Indus Waters Treaty has survived wars, diplomatic breakdowns, and decades of mistrust. But it must now evolve or risk becoming irrelevant. A well-crafted Protocol to the Indus Waters Treaty is not just an administrative update — it’s a geostrategic necessity.

Pakistan must safeguard its rights while also pushing for cooperation, climate resilience, and regional peace. With China’s participation, judicial reforms, and climate-smart provisions, the new Protocol can transform a Cold War-era treaty into a model for modern water diplomacy.