Pakistani farmers sue German polluters over catastrophic climate-linked flood damage – focus keyword: Pakistani farmers sue German polluters

Pakistani farmers sue German polluters for catastrophic climate-linked flood damage in Sindh; Pakistani farmers sue German polluters are seeking acknowledgment and compensation from major CO₂ emitters.

Pakistani farmers sue German polluters in a courageous and precedent-setting move. A group of 43 men and women from the Sindh region of Pakistan have issued formal letters before action to the German energy firm RWE and the cement producer Heidelberg Materials, warning of legal proceedings to begin later this year. The claimants say their livelihoods were decimated by the catastrophic floods of 2022, losses that they attribute—at least in part—to the historical greenhouse-gas emissions of these companies.

They seek an acknowledgement of liability and compensation amounting to approximately €1 million in respect of lost rice and wheat harvests, destroyed land and lingering disruption. If no settlement is reached, the case may proceed to court in December. This bold move places the crisis confronted by Pakistani farmers firmly into the courtrooms of global industrial emitters, signalling a new phase in climate-linked litigation.

Background: The 2022 floods and devastating impact on Sindh

The focus keyword Pakistani farmers sue German polluters must be placed early: Pakistani farmers sue German polluters after the extreme rains and floods of summer 2022.

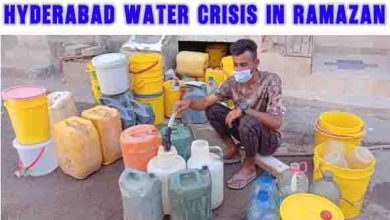

In the months from June to October 2022, Pakistan experienced what has been described as one of the most severe flood crises in its history. According to the 2022 Pakistan floods, approximately one-third of the country was submerged, over 1,700 people lost their lives and more than 33 million were affected. (Encyclopedia Britannica)

The province of Sindh bore a particularly heavy burden: satellite imagery and government surveys show that around 2.5 million hectares — over 18 % of Sindh’s area — were directly inundated, and that damaged crop land and ruined infrastructure compounded the crisis. (The Nation)

For the farmers from Sindh involved in this legal action, the floods washed away not just their fields but entire seasons of planting. Many lost multiple rice and wheat harvests. The destruction of arable land, combined with displacement, has triggered lasting economic and social hardship.

The legal claim: Who is involved, what they are demanding

The group of claimants—landowners and tenant farmers from northern Sindh (including villages such as Molabuxkhoso)—are represented by a legal team preparing letters before action that were sent to RWE and Heidelberg Materials on Tuesday. They warn that if their demands are not met, they will initiate formal proceedings before the end of the year.

Their demands:

- An acknowledgement of liability from the companies for their greenhouse gas emissions contributing to climate change.

- Compensation for destroyed harvests, flooded land and livelihoods, estimated at €1 million in total.

- A wider recognition that corporate emitters can be held accountable under the “polluter pays” principle.

One claimant stated: “We, who have contributed the least to the climate crisis, are losing our homes and livelihoods while corporations in the wealthy north continue to make profits.”

Both target companies acknowledged receipt of correspondence (in Heidelberg’s case) or indicated lack of further information (in RWE’s case). Their responses underscore the novelty and complex nature of such claims.

The defendants: German companies and their emissions footprint

RWE and Heidelberg Materials are among Germany’s largest industrial emitters. According to unpublished data from the Climate Accountability Institute, RWE is responsible for approximately 0.68 % of global industrial GHG emissions since 1965 via fossil fuel production, while Heidelberg accounts for at least 0.12 % via cement production.

These figures highlight the scale of emissions emanating from industrial “carbon majors” and provide the basis for claims that historical emissions contributed materially to climate risks faced by vulnerable communities abroad.

The legal strategy connects those emissions to the extreme rainfall and flooding event in Pakistan — thereby attempting to establish causation and liability across borders.

Significance: What this means for global climate justice and legal precedent

The move by Pakistani farmers to sue German polluters is highly significant in several respects:

- It emphasises that climate justice is no longer purely the domain of states and international agreements: affected communities are turning to litigation — raising accountability in civil courts.

- It reflects the increasing willingness of European legal systems to hear cross-border climate damage claims, as seen in parallel cases (for example, litigation by typhoon survivors in the Philippines against Shell, and the Swiss court hearing a claim brought against Holcim by Indonesian island inhabitants).

- It bolsters the “polluter pays” principle in practice: as argued by Clara Gonzales of the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, “the climate crisis is no longer a theoretical threat; it is a present reality.”

- It may pave the way for a new chapter of liability risk for large industrial emitters: by bringing claims about past harm rather than only future risk, plaintiffs hope to bypass some of the evidentiary hurdles that have hampered earlier climate litigation.

For the farmers in Sindh, the case is about much more than compensation — it is about recognition, justice and establishing responsibility in a world of climate-inequality.

Challenges ahead: Evidentiary, jurisdictional and liability obstacles

Despite the bold strategy, the path ahead is fraught with significant obstacles:

Causation and proof of linkage

The plaintiffs must demonstrate that the emissions of RWE and Heidelberg materially contributed to the extreme rainfall that caused their specific losses. Establishing such a link in court remains extremely challenging. Earlier cases (for example the one brought by mountain guide Saúl Luciano Lliuya against RWE) found that the claimant could not prove that his home was at direct risk of flooding. Nonetheless, the court there recognised theoretical corporate liability.

Jurisdiction and forum

Which court will hear the case? Will it be in Germany (where the defendants are domiciled) or elsewhere? The cross-border nature complicates procedural matters, legal standing and enforcement of judgments.

Historical emissions

Liability for historic emissions presents unique legal questions: how far back to go, how to measure responsibility, how to distribute compensation across communities and companies? The plaintiffs aim to target past harvest losses rather than future risk, which simplifies certain elements of claim (damage already incurred) but does not eliminate fundamental legal challenges.

Corporate defence

The defendants are likely to argue that they operated within legal and regulatory frameworks, that their emissions were in compliance, and that assigning retrospective liability would conflict with national law. RWE has in a previous case argued that “it would be an irreconcilable contradiction if the state permitted CO₂ emissions … but at the same time retroactively imposed civil liability for them.”

Nevertheless, by bringing the claim now, the Pakistani farmers place themselves at the forefront of climate-damage litigation and highlight the growing pressure on industrial emitters to account for loss and damage.

Conclusion: A potential turning point for “polluter pays” in climate litigation

When Pakistani farmers sue German polluters, this is a powerful signal: communities who have suffered climate-linked disasters are no longer waiting on diplomacy alone. They are pursuing justice through the courts.

The case from Sindh holds the potential to advance the global conversation on climate liability, industrial accountability and restorative justice. Even if the defendants ultimately defend the claim successfully, the very act of documentation, legal threat and negotiation may shift corporate and societal expectations.

For Pakistan, a country repeatedly ranked among the world’s most vulnerable to climate extremes, the outcome could reinforce demands for fair treatment, “loss and damage” compensation and stronger climate resilience support. For industrial emitters worldwide, the claim reinforces that historic emissions may carry future legal risk — and that the era of turning a blind eye may be ending.

In short: Pakistani farmers sue German polluters. Whether they win or lose, what they have initiated is a bold, courageous, and potentially transformative legal challenge.

External resources :

- Encyclopaedia Britannica on the 2022 Pakistan floods: Britannica – Pakistan floods of 2022 (Encyclopedia Britannica)

- Pakistan Today on Sindh damages: Pakistan Today – Sindh suffered Rs 550 b damages amid floods (Pakistan Today)

- Dialogue Earth on crop losses: Dialogue Earth – Floods after drought devastate Sindh’s agriculture (The Nation)