Pakistan floods must be a wake up call on climate action

Climate Changes News, 01/09/2022

Witnessing a human being swept away by cruel waves of flood waters while saving five stranded children is not something everyone can bear. This was my experience in early July after a torrential rainfall event in Islamabad and adjoining areas, only a short walk from my house; just a couple of months after a devastating heatwave.

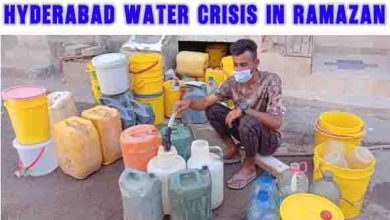

If “massive” is the word for the heatwave losses we experienced here in Pakistan, I struggle to find an appropriate one for the losses incurred from the ongoing monsoon floods. “Colossal”, “mammoth” and “gigantic” don’t do justice to what we are witnessing.

Before now, 2010 marked the year with the worst flooding in Pakistan’s history, directly affecting an estimated 14-20 million people, and killed over 1700. Nearly 1.1 million homes were damaged or destroyed, causing $9.7 billion in damages in 46 of the country’s 135 districts.

This year’s monsoon season is not over yet and the scale of destruction from the flooding is already expected to be far higher than 2010. One third of the country is suffering from floods: 30 million people.

The critical difference between the two is that the 2010 flood was mainly a riverine flood originating from the north of the country, providing a considerable lag time for regions downstream to take evacuation measures.

This time the deluge is caused by torrential rains which began in mid-June, seeing flooding outside areas that are usually prepared for such events. This is compounded by the no-less devastating riverine flooding, which has already caused the collapse of two dams in the north of the country.

As of 29 August, Pakistan’s national disaster risk management authority estimates over 1,100 casualties. Over one million homes have so far been damaged or destroyed, 800,000 livestock have been killed, 3500 km of roads have been damaged and 162 bridges have collapsed. The economic damages are likely to go well above the $9.7 billion in damages from the 2010 floods.

Pakistan is at its nadir of political stability. Thirteen political parties joined forces to oust the Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) government earlier this year, after which PTI resigned from the national assembly. PTI, however, remains in power at the provincial level and is ruling over 75% of the country’s population. In a recently-called all parties conference, PTI was not even invited, a reflection of the political bitterness, even during the time of worst flooding of country’s history.

One doesn’t need to think hard to understand how this would affect the relief activities carried out in the provinces where PTI is in power. This aspect is important to highlight because in May, the Pakistan Meteorological Department forecast a more than average rainfall in the country, warning of flash floods. But because of the political scenario, this information fell on deaf ears, including the country’s media.

To make the situation worse, Pakistan’s economy is also crippled. Pakistan was kneeling before the IMF to revive a bail-out package, including a disbursement of about $1.1 billion, to save the country from going bankrupt, funds which were released by IMF in the days after the flooding started.

With estimates of $10 billion in economic losses from the 2010 floods, a larger scale of devastation would lead to even higher level of losses.

The record-breaking heatwave in March-April this year which gripped large parts of the country, and now the worst flooding in history, are back-to-back calamities which present a classic case of what we call “loss and damage” in climate circles. Loss and damage is the loss of lives, land and infrastructure from climate impacts that cannot be recovered, nor adapted to.

A recent climate attribution study has concluded that climate change has made a 2022 heatwave across India and Pakistan 30 times more likely compared to a world without climate change. It is too early to state unequivocally (as additional studies will be conducted once the monsoon is over) but climate scientists believe that climate change will most likely have had a role in increasing the intensity of the present flooding. It certainly fits with the models and predictions of climate change driving more intense monsoons.

For a long time now, developing countries have been asking for a separate finance facility for loss and damage in the international climate negotiations under the UNFCCC.

So far, there has been resistance from the developed world to talk about the costs of loss and damage. At Cop26 in Glasgow last year a finance facility could not be agreed, despite a push from developing countries, and only a formal dialogue on loss and damage made it into the final outcome of the negotiations.

Loss and damage is likely to be a hot topic during Cop27 negotiations in Egypt this year. In the wake of this year’s record-breaking climate catastrophes it has already witnessed, it would make sense that Pakistan, as the chair of the largest group of developing countries – the G77 plus China – could make a strong case to push developed countries to agree on the establishment of a loss and damage finance facility.

This flooding must also be a wakeup call for the global community to speed up its efforts towards climate action. Pakistan emits less than 1% of global greenhouse emissions, but it is bearing a massive burden from climate change. And the large majority of the people affected are the poorest of the poor.

The devastation faced by Pakistan now is a mere precursor of what we may see at higher levels of warming. Even at the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C warming limit, some of the impact of climate extremes will go beyond the tolerable limits of human and natural systems.

As the world continues on its go-slow in getting out of fossil fuels and decarbonising the global economy, the losses and damage will continue to mount, and countries like Pakistan – and those others suffering damage they cannot pay for – need financial support.