How Pakistan’s Flood Crisis Bends Climate Talks Towards Reparations

Bloomberg.com, 9 October 2022

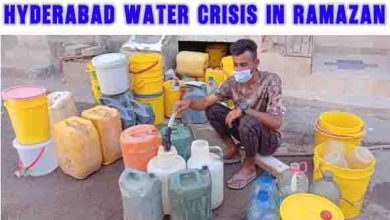

This summer’s destructive floods have left 21 million Pakistanis in desperate need of help weeks after flooding peaked, and the United Nations is still scrambling for resources to deliver life-critical aid to even half that number. As acting head of the UN humanitarian agency’s work in Pakistan, Ruth Mukwana has spent recent days traveling through washed-out provinces of Sindh and Balochistan. The highways are filled with children and mostly women living in makeshift tents without access to clean water, appropriate nutrition or sanitation.

“These communities really have not created the climate crisis, and yet they’re the ones bearing the brunt of it,” says Mukwana in an interview.

Aid organizations will work for months and years to help Pakistanis recover. But that support will be temporary in nature, even as the country faces down an enduring new era of climate vulnerability and grave risk to its population. “Ultimately, the world has to be able to help the people of Pakistan stand again on their feet,” she says.

In remarks on Friday, UN Secretary General António Guterres implored member countries to contribute to Pakistan’s aid. The death toll from flooding now stands at 1,700, but he warned that malaria, cholera and other diseases spreading in the aftermath “threaten to claim far more lives than the floods.”

“We are still in the life-saving phase after 17 hard weeks,” Sherry Rehman, the minister of climate change for Pakistan, said Friday in an interview to Bloomberg TV.

ew countries are as vulnerable as Pakistan. Its cities regularly record some of the hottest temperatures in the world, including a springtime heat wave this year made 30 times more likely by greenhouse gases. That set the stage for summer monsoons that saw rainfall reach an intensity more than 50% greater than would have been the case without planet-warming pollution. Both findings come from World Weather Attribution, a leading research group that delivers rapid analysis of the link between extreme weather and climate change.

This is one example of powerful new evidence in the moral and political argument for climate reparations. As diplomats and world leaders prepare for next month’s annual UN climate summit, known as COP27, there’s likely to be renewed focus on the long-running dispute over who should pay for the devastation wrought by rising temperatures. Speeches and closed-door negotiations will involve calls for payments from high-emitting countries, most of which are wealthier and less vulnerable, to their low-emitting counterparts that suffer climate impacts. The debate will be informed by the blatant suffering visible on the ground in Pakistan as well as new data on exactly who is responsible for atmospheric pollution.

Working with colleagues from Bloomberg’s data-visualization team, I took a deep look at cutting-edge research into economic attribution for climate damage. Two Dartmouth researchers, Christopher Callahan and Justin Mankin, recently published a study and data estimating for the first time how much economic growth, in terms of GDP, has been lost to developing countries as a result of burning fossil fuel. It’s striking to see estimated dollar figures linking the pollution by the two biggest emitters, the US and China, to more than $60 billion in economic loses for Pakistan.

Together, the US and China have created enough atmospheric impact to cost the world about $1.8 trillion. The US alone was responsible for 16.5% of global GDP losses from climate change from 1990 to 2014, according to research by the Dartmouth team. (Check out the full story in Bloomberg Green to see the eye-opening graphics explaining this economic research as well as satellite data tracking the destruction in Pakistan.)

Mukwana’s experience driving through flooded provinces and walking along highways that have become makeshift homes for displaced people unifies the personal and the global in ways few will ever experience. That’s because the people pushed aside by flood waters are, in part, victims of a problem even bigger than the monsoon.

UN climate negotiations for many years focused almost exclusively on preventing new emissions and the resulting rise of global average temperatures, a concept called “mitigation” in climate jargon. Diplomats and politicians have also taken up the question of “adaptation” — how nations might find the resources to afford greater resiliency. But Pakistan’s crisis has renewed emphasis on a more often ignored section of the 2015 Paris Agreement that deals with a concept called “loss and damage.”

Since the steepest costs of today’s climate continue to be borne by populations that emitted the least, recognizing loss and damage could mean that nations who gained the most from burning fossil fuel should pay compensation. It’s a vision of climate reparations — and it’s long been opposed by wealthy nations.

When nearly 200 national delegations meet next month for COP27 in the Egyptian resort of Sharm El-Sheikh, loss and damage is expected to eclipse most other topics on the agenda. In part this stems from the coincidence that a Pakistani diplomat is currently the leader of the largest bloc of developing nations, known as the G77+China. The Egyptian hosts of this summit are also members of the bloc.

Loss and damage has struggled to rise up the agenda for years. Developing nations last year went to COP26 talks in Glasgow, Scotland, pushing for a formal process for dispatching finance and technical help paid for by developed nations. That summit ended with only a loosely defined “dialogue” on the topic. There are fresh indications that loss and damage may be treated with greater attention than ever before at COP27, even if it’s with “diverse views on the scope and timeframes” of how to tackle the issue, according to a briefing shared on Friday by Ed King, a climate media and policy strategist.

If or when countries agree on a structured way to help people deal with climate disasters, it won’t come fast enough for the millions suffering from this year’s monsoon rains in Pakistan. Estimates of damage have tripled to $30 billion since the end of August. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, which Mukwana represents in Pakistan, this week raised by a factor of five its initial aid goal, to $816 million, to pay for triage support through May 2023. Those funds might help blunt a rapidly emerging public-health crisis. But it can’t compensate Pakistan for the brutal consequences of other people’s emissions.

“How much can people go through these cyclical kinds of events?” Mukwana asks. “How much of it can people take?