How does climate change influence wellbeing?

“The time has come to treat the climate and nature emergency as a worldwide wellbeing crisis,” says a source of inspiration distributed in north of 200 wellbeing diaries in the run up to the 2023-24 COP gatherings on climate change and biodiversity.

Dr Zulfiqar A. Bhutta, Founding Director of the Focal point of Greatness in Ladies and Youngster Wellbeing and the Foundation for Worldwide Wellbeing and Advancement at the Aga Khan University (AKU), is very much acquainted with how factors past the conventional circle of wellbeing – whether in food security, struggle or climate – influence the most helpless. On World Kids’ Day, he investigates how to advance the circumstance of moms and youngsters.

Who endures the worst part?

“A portion of the difficulties around orientation, especially the intensity impacts of climate, are not notable. Furthermore, regardless of whether they are perceived, there aren’t numerous arrangements set up.”

Ladies are almost certain than men to telecommute, and more unfortunate quality lodging, lacking power to control fans, or running water, traps numerous in unpreventable intensity. Additionally, those without an indoor restroom may not hydrate to try not to need to pee during long days inside. In an intensity wave, this fundamentally builds the dangers of drying out and demise.

For pregnant ladies, outrageous intensity builds the gamble of premature delivery, early work and birth difficulties. Universally north of 20% of kids under five are stunted, yet this isn’t each of the a result of lacking nourishment:

“Heat openness in pregnant ladies immensely affects birth results, possibly even intergenerational impacts,” says Dr Bhutta. “In Pakistan, we’ve found that a ton of the youth stunting somewhat recently or two is really connected with possible openness to natural intensity. Baby death rates might increment by a quarter because of the impacts of climate change. Be that as it may, this is preventable. We grasp the series of arrangements.”

Baby death rates might increment by a quarter because of the impacts of climate change. Be that as it may, this is preventable.

Changing precipitation designs are influencing harvests and causing unhealthiness, with ladies frequently especially denied when family assets are restricted. At the point when food is scant, they eat not as much as men.

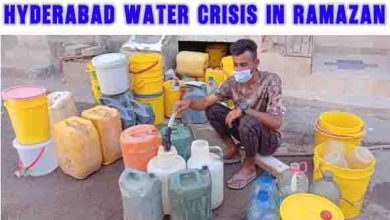

At the point when floods or other climate-exacerbated calamities obliterate or forestall admittance to medical care arrangement, or even power community dislodging, the wellbeing suggestions are huge. Climate change additionally expands the spread of vector-and water-borne diseases like dengue fever and typhoid. “On the off chance that you are water-unreliable, you can well envision the gamble to farming and food security, and the outcomes as diarrhoeal problems go up.”

Dr Bhutta adds, “A portion of the emotional wellness focuses on that climate change presents are lopsidedly bunched among young individuals, since they don’t see a future in that frame of mind of climate change. They get affected by this significantly more than someone who’s now in their 80s or 90s.”

Young individuals don’t see a future in that frame of mind of climate change.

How might wellbeing studies make change?

Dr Bhutta has been working in kid and maternal wellbeing since the 1970s, saying “Ladies and kids, especially young kids, should be at the focal point of the feasible improvement objectives for us to arrive at our human resources potential.”

One of his initial examinations found that in South Asia, over portion of infant and baby passings happened in town or rustic settings, in the areas with least wellbeing specialist co-ops. He tried whether empowering Pakistan’s Woman Wellbeing Laborers to undertake outreach with gatherings of pregnant ladies could lessen neonatal mortality in rustic Sindh and saw such a huge decrease of stillbirths and neonatal mortality that he sent his group to reverify their numbers. India would before long embrace this training for its Asha wellbeing laborers, exhibiting what huge scope execution examination can mean for strategy and influence whole populaces.

As he approaches the finish of his forty years at AKU, with a variety of grants and high level situations in his possession, Dr Bhutta is driving three global examinations to further develop youngster and juvenile wellbeing and nourishment, address ladies and kids’ wellbeing in philanthropic and struggle settings, and tackle the difficulties of climate change and wellbeing for ladies and youngsters in danger populaces in South Asia. How could he integrate such shifted factors while attempting to work on maternal and youngster wellbeing?

What else can safeguard the defenseless?

At the point when the 2010 floods uprooted near 10 million individuals in Pakistan, his examination bunch at AKU laid out wellbeing camps that treated more than 1,000,000 individuals. “It turned out to be extremely obvious to me around then that there were a few things beyond the standard wellbeing framework that influenced the wellbeing, prosperity and sustenance of ladies and kids. One of those was climate change. One more was that issues in delicate populaces, for example, clashes or uprooting likewise impacted what we could or couldn’t do. Very nearly 40% of the weight of passings in kids and ladies and babies are in topographies impacted by polycrises, not a solitary issue. So I began to contemplate what should be possible with regards to building versatility.

“In Pakistan exactly quite a while back, there was an outrageous intensity occasion in Karachi that killed around one and a half thousand individuals in a solitary day, the greater part of them kids. Also, that happened on the grounds that no one was ready for it. No one perceived the difficulties of families and kids living in metropolitan ghettos which become like broilers in the intensity of the mid year.

“That prompted legislative mediations like hotlines, crisis administrations and early admonition frameworks. Be that as it may, communities likewise coordinated themselves to work in flexibility with both water supply and volunteers who could safeguard the people who were at most serious gamble. We have had occasions since which have been comparably serious. However the mortality was not even close as high. We believe that we can additionally work on the association of rustic communities around safeguarding ladies, kids and the old from the outcomes of climate.”

We can’t simply see what’s going on. We should be in the cutting edge of the discussion.

Dr Bhutta sees a support job for pediatricians such as himself. “We can’t simply see what’s going on. We should be in the cutting edge of the discussion with legislators as far as how significant this is to address, and to ensure that procedures are proof based. You can’t give a pill for climate change. No one will trust that fossil fuel byproducts will descend and afterward the effect becoming apparent downstream.

“You must effect lives and livelihoods. We want social security, support for people affected by climate change, which isn’t really inside the domain of wellbeing services. Working with our provincial communities around farming, food security and biodiversity will be a vital piece of the climate reaction. Furthermore, building vital coordinated efforts with different accomplices and projects is critical.

“The northern and southern halves of the globe are not various universes. Climate change influences everyone and the results needn’t bother with international IDs or visas.” “It is time to treat the climate and nature crisis as a global health emergency,” says a call to action published in over 200 health journals in the run up to the 2023-24 COP meetings on climate change and biodiversity.

Dr Zulfiqar A. Bhutta, Founding Director of the Centre of Excellence in Women and Child Health and the Institute for Global Health and Development at the Aga Khan University (AKU), is all too familiar with how factors beyond the traditional sphere of health – whether in food security, conflict or climate – affect the most vulnerable. On World Children’s Day, he explores how to improve the situation of mothers and children.

Who bears the brunt?

“Some of the challenges around gender, particularly the heat effects of climate, are not well known. And even if they are recognised, there aren’t many solutions in place.”

Women are more likely than men to work from home, and poorer-quality housing, lacking electricity to power fans, or running water, traps many in inescapable heat. Moreover, those without an indoor latrine may not drink water to avoid having to urinate during long days inside. In a heat wave, this significantly increases the risks of dehydration and death.

For pregnant women, extreme heat increases the risk of miscarriage, early labour and birth complications. Globally over 20 percent of children under five are stunted, but this is not all a consequence of inadequate nutrition:

“Heat exposure in pregnant women has an enormous impact on birth outcomes, potentially even intergenerational effects,” says Dr Bhutta. “In Pakistan, we’ve discovered that a lot of the childhood stunting in the last decade or two is actually related to potential exposure to environmental heat. Infant mortality rates may increase by a quarter due to the effects of climate change. But this is preventable. We hold the strings of solutions in our hands.”

Infant mortality rates may increase by a quarter due to the effects of climate change. But this is preventable.

Changing rainfall patterns are affecting crops and causing malnutrition, with women often particularly deprived when household resources are limited. When food is scarce, they eat less than men.

When floods or other climate-exacerbated disasters destroy or prevent access to healthcare provision, or even force community displacement, the health implications are significant. Climate change also increases the spread of vector- and water-borne illnesses like dengue fever and typhoid. “If you are water-insecure, you can well imagine the risk to agriculture and food security, and the consequences as diarrhoeal disorders go up.”

Dr Bhutta adds, “Some of the mental health stresses that climate change poses are disproportionately clustered amongst young people, because they don’t see a future in the wake of climate change. They get impacted by this much more than somebody who’s already in their 80s or 90s.”

Young people don’t see a future in the wake of climate change.

How can health studies create change?

Dr Bhutta has been working in child and maternal health since the 1970s, saying “Women and children, particularly young children, need to be at the centre of the sustainable development goals for us to reach our human capital potential.”

One of his early studies found that in South Asia, over half of newborn and infant deaths occurred in village or rural settings, in the areas with fewest health service providers. He tested whether encouraging Pakistan’s Lady Health Workers to undertake outreach with groups of pregnant women could reduce neonatal mortality in rural Sindh and saw such a significant reduction of stillbirths and neonatal mortality that he sent his team to recheck their numbers. India would soon adopt this practice for its Asha health workers, demonstrating how large-scale implementation research can influence policy and affect entire populations.

As he nears the end of his four decades at AKU, with an array of awards and top-level positions to his name, Dr Bhutta is leading three international studies to improve child and adolescent health and nutrition, address women and children’s health in humanitarian and conflict settings, and tackle the challenges of climate change and health for women and children in at-risk populations in South Asia. How did he incorporate such varied factors when working to improve maternal and child health?

What else can protect the vulnerable?

When the 2010 floods displaced close to 10 million people in Pakistan, his research group at AKU established health camps that treated over a million people. “It became very clear to me at that time that there were several things outside of the mainstream health system that impacted the health, well-being and nutrition of women and children. One of those was climate change. Another was that problems in fragile populations such as conflicts or displacement also had a big influence on what we could or could not do. Almost 40 percent of the burden of deaths in children and women and newborns are in geographies affected by polycrises, not a single problem. So I started to think about what could be done in terms of building resilience.

“In Pakistan some eight years ago, there was an extreme heat event in Karachi that killed about one and a half thousand people in a single day, more than half of them children. And that happened because nobody was prepared for it. Nobody recognised the challenges of families and children living in urban slums which become like ovens in the heat of the summer.

“That led to governmental interventions like hotlines, emergency services and early warning systems. But communities also organised themselves to build in resilience with both water supply and volunteers who could protect those who were at greatest risk. We have had events since which have been just as severe. Yet the mortality was nowhere near as high. We think that we can further improve the organisation of rural communities around protecting women, children and the elderly from the consequences of climate.”

We can’t just observe what is happening. We need to be in the frontline of the debate.

Dr Bhutta sees an advocacy role for paediatricians like himself. “We can’t just observe what is happening. We need to be in the frontline of the debate with politicians in terms of how important this is to address, and to make sure that strategies are evidence-based. You can’t give a pill for climate change. Nobody’s going to wait 30 years for carbon emissions to come down and then the impact becoming visible downstream.

“You’ve got to impact lives and livelihoods. We need social protection, support for individuals impacted by climate change, which is not necessarily within the purview of health ministries. Working with our rural communities around agriculture, food security and biodiversity is going to be a very important part of the climate response. And building strategic collaborations with other partners and programmes is extremely important.

“The northern and southern hemispheres are not different worlds. Climate change impacts everybody and the consequences don’t need passports or visas.”