How climate change is changing Pakistan’s rainstorm driven seaside landscape

Pakistan: Showing up before the expected time July, the rainstorm in Pakistan is a mind boggling peculiarity that has become progressively unpredictable and whimsical because of climate change. Pakistan is one of the countries most uncovered and battered by these interruptions.

On a road in Pakistan’s national capital, Islamabad, stands the brand-new National Crisis Tasks Center (NEOC). Inside an immense room suggestive of a NASA space focus, with walls canvassed in goliath screens showing information from 17 satellite sources and thousands of measurements, many specialists are attempting to understand the ramifications of outrageous climate events, from ice sheet melts to floods.

In when seasons are speeding up and nature is becoming unpredictable, researchers from different disciplines — climatology, meteorology, seismology, glaciology, and hydrology — are assembled here to expect debacles and potentially save lives. “We depend on innovation to survey dangers and issue alerts,” made sense of Syed Tayyab from his command post. “We screen, for instance, floods that can be brought about by frosty lake explosions, as well as torrential slides, blizzards, and cold waves.”

The storm, which showed up sooner than expected July, doesn’t look good: gauges recommend that 200,000 Pakistanis could be impacted by over the top downpours, provoking a crisis reaction plan of $40 million.

Finished in October 2023 at an undisclosed expense, the aggressive NEOC, under Pakistan’s National Catastrophe Management Authority, was the country’s reaction to the grievous floods throughout the mid year storm of 2022. In the midst of a scriptural downpour, the Indus Waterway and its feeders spilled over, lowering 33% of the country. In the bedlam and fierceness of the waters, more than 1,700 Pakistanis lost their lives. The size of the obliteration brought this striving country, currently tormented by political and monetary emergencies, to its knees, and it presently can’t seem to recuperate.

Feared start to the rainstorm

In South Asia, the rainstorm starts every year in the Indian province of Kerala toward the finish of May or early June. The downpours then move upper east to arrive at Bangladesh by mid-June prior to moving northwest, evading the Himalayan wall. It regularly shows up in Pakistan during the primary seven day stretch of July and pulls out by mid-September. “The storm, which in Arabic signifies ‘occasional breezes,’ is one of the planet’s most efficient climate frameworks,” said Abdul Qadir Khan, a climate change expert at Punjab University in Lahore.

Before it shows up, outrageous climate events happen: spring brings exchanging downpours and unprecedented intensity spikes, fueling ice sheet liquefies and evaporating fields. So when the helpful downpours show up, bringing 3/4 of the yearly precipitation, they are commended by the 2 billion occupants of the Indian subcontinent.

Ladies wear delightful saris to respect the rainstorm, which is essential for agribusiness and food security. As the breezes blow, kids fly kites that euphorically dance overhead loaded up with weighty dark mists. Celebrated in expressions and customs, the storm rouses consideration, verse, and sentiment. In Bollywood, romantic tales generally unfold under sexual and soothing downpours.

The storm has for some time been the musicality of life. Like the snow on the most elevated Himalayan pinnacles, it should be timeless. A “great rainstorm” guarantees the financial strength of a whole country. “The prospering of early human advancements, similar to that of the Indus Valley, was supported by the moderate climate made by the rainstorm,” noted Khan.

Unpredictable and rough rainstorm

Today, nonetheless, it has become unpredictable and rough. “Because of climate change, the rainstorm’s atmospheric condition is upset,” the climate change expert proceeds. “Downpours will generally begin later. In Pakistan, they likewise pull out later. As indicated by my perceptions, the rainstorm zone even appears to broaden toward the west and toward the north into Afghanistan.”

A new report by the World Climate Attribution expresses that “climate change increments outrageous precipitation during the storm.” The Intergovernmental Board on Climate Change likewise accepts that climate change worsens the force of the downpours.

This peculiarity is supposed to heighten in the 21st hundred years, joined by more regular serious intensity and mugginess waves. “Researchers have likewise found that the ‘Indian Niño,’ a peculiarity that triggers warming in one piece of the Indian Sea and cooling in another, straightforwardly influences the rainstorm and makes disturbances from Australia East Africa,” Khan added.

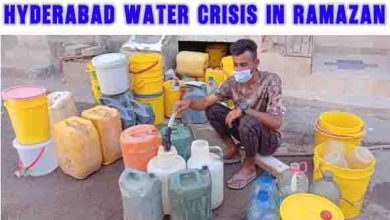

At the point when the rainstorm hits Pakistan, the precarious landscape, a gift for farming water system frameworks, turns into a bad dream. Downpours rush down the slants, driven by spilling over streams and inadequately kept up with waterways. “Subsequently, in 2022, whole towns were cleared off the guide,” bemoaned Qais Aslam, a financial specialist and political expert in Lahore.

Waterway arrangements at the core of pressures

“Climate change? I don’t have the foggiest idea what that is,” conceded Shaukat Ali, a rancher by the Ravi Stream in Punjab, watching out for his plot of land, bison, and cows. “However, I’m utilized to floods. We move farther away with the cows at whatever point the waterway takes steps to spill over.”

His neighbor, Muhammad Zakaria, donning a white facial hair growth, smokes a hookah under a bamboo cover. Shaking his head, he said: “Climate change and floods are India’s shortcoming! They open their dams and flood us at whatever point they need.”

Pakistan’s significant streams drop from Tibet and India, and waterway settlements are a wellspring of increased strains. “We intently screen Indian dams upstream as they can modify the progression of our waterways,” recognized Tayyab at the NEOC.

In 2022, cotton, rice, and sugarcane crops were assaulted. And the establishing season no longer lines up with the impulses of the storm. “Climate change continues to ruin us,” mourned Khaled Mehmood Khokhar, leader of Pakistan’s biggest ranchers’ affiliation. “Besides, farming exploration is at a standstill; representatives at the National Horticultural Exploration Institute in Multan haven’t been paid for quite some time.”

The eighth most weak country to the climate emergency

As indicated by the NGO Germanwatch, Pakistan positioned eighth among the countries generally helpless against the climate emergency from 2000 to 2019. However, it isn’t answerable for an Earth-wide temperature boost, as it delivers under 1% of worldwide ozone depleting substance discharges. “We endure while it’s not our issue,” Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif censured in 2022, highlighting the obligation of rich countries.

Confronting the climate emergency, Pakistan is pushed to its furthest reaches of versatility. The political and financial setting doesn’t help. Public specialists are restricted, government and common offices are ineffectively planned, and defilement stays endemic. In the background, the military is in charge, as exemplified by the NEOC focus in Islamabad, drove by a high-positioning officer. “In catastrophe management, our administration depends on the military rather than its own association, fueling the inefficiency of our country,” Aslam said.

“The disturbance of the rainstorm could be the most obliterating climate peculiarity in the subcontinent,” predicts university professor Khan. “The appearance, withdrawal, and rainstorm examples will change throughout the next few decades. It’s difficult for all of mankind.” For the present, a shade of downpour falls over Pakistan, which has quite recently proclaimed a condition of caution.

On the bleeding edges of climate change

— Pakistan has 7,000 glacial masses and 3,044 frigid lakes, 36 of which are in danger of breaking without warning.

— As per the World Bank, climate change has impacted 75 million Pakistanis more than thirty years. Rural and biodiversity misfortunes cost $1 billion every year.

— The 2022 floods brought about 1,700 passings, north of 1 million domesticated animals killed, 2 million houses annihilated, and 13,000 kilometers of streets crushed.

— The expense of such obliteration is assessed at some $16 billion. The $10 billion vowed to Pakistan by the international community has not been gotten. Just 5% of the annihilated houses have been reconstructed.