How climate change affects youth mental health in Pakistan

- In 2024, Pakistan has faced devastating floods and extreme heat, hindering its recovery from existing climate crisis-related disasters.

- While the economic and physical health impacts of climate change are clear, Pakistan’s population is also experiencing the often overlooked mental health ramifications.

- How can a growing sense of climate anxiety or “eco-anxiety” in locals be addressed?

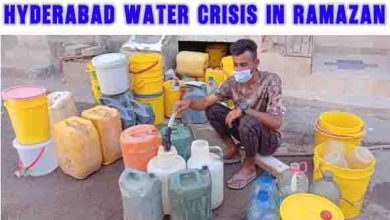

Pakistan is facing an onslaught of climate disasters. Since record floods in 2022 that affected 33 million residents and caused more than $15 billion in damages, the country has contended with several new crises that have hampered a sustained recovery.

In February 2024, flash floods further upended lives and livelihoods in the southwestern coastal region of Gwadar – the heart of a billion-dollar investment under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. The summer of 2024 has been marked by searing heat with thousands of Pakistanis succumbing to heatstroke and inundating healthcare facilities.

Yet, while the economic and physical health impacts of climate change are clear, Pakistan’s population is also experiencing the often overlooked mental health ramifications. The devastating fallout from the floods and extreme heat have stoked a sense of climate anxiety or “eco-anxiety” in locals, a term popularly used to convey despairing sentiments around the climate crisis. Profound unease and uncertainty about how relentless climate disasters could diminish quality of life are deeply felt, even if not always articulated.

While the impacts of eco-anxiety are somewhat better documented in developed nations, places like Pakistan – classified as among the most climate-challenged countries – offer a prime opportunity to better probe these effects in the developing world.

To better understand how Pakistanis are grappling with eco-anxiety, we spoke with dozens of individuals living in low-cost, climate-resilient houses in the Sohbatpur district of Balochistan, Pakistan’s largest province.

These newly constructed houses, specifically designed to shelter victims of climate change-fuelled disasters, are the brainchild of a multinational partnership involving Balochistan Youth Action Committee, British Asian Trust, Deutsche Bank and HANDS Pakistan. Our interactions with these residents, who have experienced the brunt of the climate crisis, revealed three crucial themes that could chart a path to address eco-anxiety in vulnerable regions.

1. Women and young people are distinctly impacted by climate shocks

Climate change disproportionately affects the mental health of women and youth, whose needs and concerns are often sidelined during major climate disasters. Moreover, these disasters can create a state of disorder that diverts resources away from alleviating prevailing inequities, instead deepening them.

Several of the women we spoke to suggested that climate events tend to disrupt community networks that are critical for Pakistani women’s social support, in turn heightening feelings of isolation and anxiety. Not to mention, these disasters can potentially expose them to additive traumatic circumstances, consistent with reporting that early marriages and intimate partner violence surge during times of climate change-driven instability.

Pakistani youth are also at elevated risk of mental health impacts from climate change. A looming concern that emerged from our conversations with young people revolved around missed educational prospects, as schools have been forced to close owing to the floods. The young people we spoke with shared profound concerns about lagging behind academically. The shift to survival mode without their school-based support system – mirroring the community deficits felt by women – causes additional distress.

Moreover, the young experience eco-anxiety rooted in uncertainty about future job opportunities. This interplay of educational and employment challenges, brought into sharp focus by the climate crisis, calls for youth-oriented solutions to target their unique mental health struggles.

2. Stigma surrounding mental health is difficult to break

Mental health is already a heavily stigmatized topic in Pakistan, often associated with notions of witchcraft or evil spirits. Adding the dimension of mental health struggles connected to climate disasters further complicates this delicate discourse. Several young people we spoke to appreciated the importance of mental health but emphasized that pervasive taboos around the subject discouraged them from seeking support.

Comparatively, many of the older seemed significantly less familiar with mental health as a general concept, even struggling to find the corresponding term for it in their local dialect. Others expressed scepticism about the utility of mental health care services, despite approximately 50 million Pakistanis facing some variety of mental health challenges. The scarcity of culturally sensitive resources to facilitate conversations about eco-anxiety, in addition to the lack of specialized mental health training for first responders in climate disaster scenarios, underscore critical opportunities for improvement.

3. The intergenerational divide on climate action persists

Another throughline that emerged is the generational gap in perspectives on climate issues, particularly the importance of climate action to help mitigate eco-anxiety. The younger Pakistanis surveyed were passionate about championing climate causes and conveyed interest in working towards sustainable solutions for their community. However, older people often described climate change with rhetoric such as “God’s will”, highlighting contrasting views on whether individuals have the capacity to improve climate outcomes and decrease the underlying causes of eco-anxiety.

Closing this intergenerational divide through informed dialogue and collaborative objectives is vital. Implementing “climate cafes” or discussion spaces designed for sharing complicated feelings about climate change and uncovering avenues for action, may prove a useful starting point.

A way forward

Despite having a negligible environmental footprint, communities like the district of Sohbatpur in Pakistan are enduring the worst of the climate shocks and bearing a serious – though underreported – mental health burden as a result.

The stories of these residents are emblematic of a broader challenge in addressing the unique contours of eco-anxiety across the developing world, where pervasive inequities, scarce mental health support and wide generational differences can exacerbate the problem. Adapting strategies that foster culturally sensitive conversations and promote nurturing spaces would constitute a critical step forward.