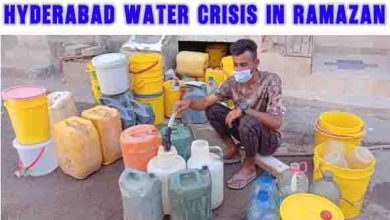

EVEN now, when crop yields have declined, cattle are dying, agricultural lands are parched and millions do not have enough water for their basic needs, there is little sign that the authorities are as alarmed as they should be over the current drought emergency. For a long time now, international bodies have been warning that water resources in Pakistan will dry up by 2025. That the country’s per capita water availability has dropped from 5,060 cubic metres per annum in 1951 to a mere 908 cubic metres today,

according to UNDP estimates, is a depressing measure of things to come. Despite the facts, warnings and signs, comprehensively tackling the water crisis issue does not appear to be on either the government’s or any political party’s agenda. Decades of short-sighted development and consumption practices have turned the rivers in the country into cesspools of toxic waste. Nearly 92pc of the Indus delta, once known for its immensely rich flora and fauna, has been destroyed while the river itself now resembles a nullah overflowing with plastic waste.

Meanwhile, the Ravi is listed among the three most polluted rivers of the world, while freshwater lakes such as Manchhar and Keenjhar are also badly polluted and have contracted in size. All this is a searing indictment of the state’s policies and its mismanagement of the country’s water resources that are necessary to sustain life, business and growth.

Pakistan’s failure on this front will ensure an even more catastrophic impact of climate change, to which the current drought in the country is intrinsically connected. The ongoing heatwave, which has severely aggravated the prevailing water shortage, illustrates this. Consider Federal Water Resources Minister Khursheed Shah’s claims in the National Assembly on Friday that up to 6,000 cusecs of water “evaporated” while travelling a distance of 350km from Sukkur to Kotri barrages.Moreover, new research indicates that severe heatwaves, of the kind estimated to have taken about 90 lives in India and Pakistan this year, will now be the new normal as they are 30 times more likely to occur than before. Meanwhile, the dreaded rise of 2°C in global temperatures might translate into an exponential increase of up to 20°C in South Asia. If this does not call for steps to stop our wasteful ways, revive dying water bodies while protecting and conserving the limited water resources we have on a war footing, then what will?

PulTR CChfDzS SIbueMWj GZMQnU KShZ