An glacier mass child is conceived: Mating glacial masses to supplant water lost to climate change

CHUNDA, Pakistan – A rancher and a town chief in Pakistan’s high countries concluded the time had come to attempt to make a glacial mass child.

This antiquated custom that calls for blending pieces of white ice sheets, which inhabitants accept are female, and dark or earthy colored glacial masses (whose variety comes from rock garbage), which occupants accept are male.

People accept that consolidating the pieces will ignite the production of an infant glacier mass that will eventually become large to the point of filling in as a water hotspot for ranchers.

The custom blurred many years prior as innovation came to Baltistan. Yet, it’s getting another glance as human-prompted planetary warming overturns life here, as per occupants, nearby specialists and researchers at ICIMOD, the boss intergovernmental body that concentrates on climate change in Asia’s high mountains.

What’s more, it has a far-fetched patron: the Unified Countries, which gives little awards of two or three hundred bucks for glacier mass mating and the assistance of a master on designer’s Balti customs.

The Assembled Countries Improvement Program (UNDP) is hoping to assist inhabitants of northern Pakistan with adjusting to climate change – inclining toward the area’s native culture to track down ways of supplanting the quickly softening glacier masses.

Glacier mass mating is one of a few flighty procedures they are attempting. The water deficiencies in this Himalayan locale are likewise provoking ranchers to adjust an adjoining Indian procedure of building frozen drinking fountains. An architect is attempting to gather torrential slides. Then there’s a gathering of ladies who consider themselves the “water criminals.”

“We are trying in vain. Like an individual suffocating, we will take a stab at anything,” says Shamsher Ali, a 65-year-old senior in the town of Machulo, where water robbery is overflowing.

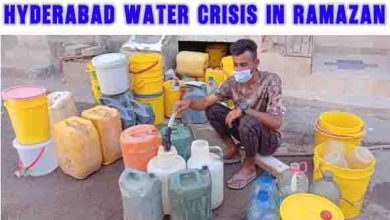

Water deficiency in a place that is known for ice

It might come as a shock that inhabitants of this hilly locale face water shortage. The far northern Pakistani domain of Baltistan frames some portion of Asia’s high mountains, enveloping the Himalayas, the Karakoram and Hindu Kush ranges. It is frequently in need of help as the “Third Shaft” since it holds the world’s biggest volume of ice beyond the polar districts.

For ages, Chunda’s occupants have depended on glacier mass liquefy to water their little fields of wheat and grain as well as their plantations of almonds, cherries and apples. The postcard-pretty town showed up genuinely lavish on a new day, as a shepherd fought his run between stone walls isolating fields of pre-summer crops. However, rancher Yasin Malik, 31, highlighted close by slopes where he once developed almond plantations. The slopes had become infertile and dry after adjacent ice sheets immediately withdrew.

The a great many glacial masses settled in these taking off mountains have been liquefying all the more quickly throughout the course of recent many years. Some are framing shaky lakes that breakdown, sending ice and stones down mountains, obliterating terrains, streets and homes. There are a bigger number of torrential slides than previously, says Ejaz Karim, the head of crisis the board for the Agha Khan Organization for Territory, a not-for-profit that intently screens effects of climate change nearby. Indeed, even as wrecking floods become more normal, snowfall has diminished, meaning less spring snowmelt for streams going from Machulo’s mountain stream to the wild Shyok waterway.

About 80,000 occupants live in regions previously thought to be excessively risky for residence in view of the effects of climate change, says Karim. One of those occupants is Sheherbano Rajput, a 25-year-elderly person who lives close to Terrible Smack, a town wedged between a stream and the lofty grades of the Hindu Kush. Last year, downpours overflowed their territories and set off avalanches that crushed through their town. Seven months pregnant and gripping her newborn child little girl, Rajput ripped at through mud and rock to somewhere safe and secure. Rajput says presently she’s frightened at whatever point it downpours. “I continue to ask myself, when, when, when, will it reoccur?”

This large number of effects are supposed to decline, as per a report delivered in June by ICIMOD. Regardless of whether people can keep a worldwide temperature alteration to somewhere in the range of 2.7 and 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit constantly 2100, Asia’s high mountains are supposed to lose 30%-half of their ice mass before the century’s over. That ice mass is a significant hotspot for 10 significant Asian stream frameworks that give water to a few 1.9 billion individuals.

For the time being, occupants are attempting to adjust to their quickly evolving reality, helped by specialists, help gatherings and the U.N.. “It’s an issue of tending to what we can,” says Knut Ostby, the occupant delegate for the UNDP, in Pakistan. He says the science behind the custom of glacier mass mating is sound.

The cold mating game

A mountain hydrologist who centers around Asia’s high mountains, Jakob Steiner, concurs. Local people recover ice from lower down the mountain, where it is dissolving, “and you take it further up” where it can’t liquefy, he says.

“They put it into caves, where [the ice is] concealed from sunlight based radiation,” he says. “It’s a lot colder. Pouring on top too is going. So it will freeze — so that ice really develops,” he says. “You can do this over seasons, on the grounds that at that height it doesn’t soften.”

For the glacial mass child project, town pioneer Saeed Baltistani thumped on entryways and persuaded handfuls regarding men, including his companion, the rancher Malik, to embrace the tiring custom during a Himalayan winter. Chunda inhabitant Mukhtar, who just has one name, drove men on a four-day stroll through weighty snow to arrive at a mountain where, his elderly folks told him, the best female glacial masses could be found. The men scaled the mountain and crushed off lumps of white ice sheets with demo hammers.

Malik drove different men up K2, or Chhoghori, the world’s second most noteworthy mountain, to track down the best male ice sheets. Malik works occasionally as a doorman for mountain climbers, so it was a trip he knew well. “For quite a long time I was noticing the most grounded male ones,” he smiled.

It took the men more than seven days to arrive at the male ice sheets. They returned, frostbitten and weighed down with pieces of valuable ice. Then, at that point, following a custom of noticing quiet during the custom mating process, the men assembled in Chunda and quietly walked many feet up their nearby mountain, conveying the glacier mass lumps. They found a huge cleft close to a mountain stream, similar to an underground room, where they set down waste as wheat husks and coal. A town minister put the male ice sheet lumps on this bed. Then the workers added the female pieces. They poured spring water over them and covered them with more coal and waste. The priest presented a few sections of the Qur’an.

Steiner, the hydrologist, says adding debris, coal and different materials is a method for keeping ice frozen longer. By wrapping up the ice with harsher surfaces, the water that melts turns into a slurry, as opposed to a stream. It moves all the more leisurely thus has a more prominent possibility refreezing, especially by night when temperatures decrease in these high heights.

The men likewise butchered a goat they drove up the mountain, trusting the extra blood penance could win some genuine blessing. (All the more mundanely, Baltistani said the men got eager and had a grill.) Then, at that point, they made a beeline for their town and paused.

Monitoring the child ‘glacial mass’

Two years after the men of Chunda attempted to mate glacial masses and make a glacial mass child, Baltistani, the nearby town pioneer, took NPR journalists to visit the site. Following a day-long trip past shepherds feeding goats, through mists puffy with downpour and over smooth rocks, Baltistani finally showed up. His face fell. The glacier mass child was as yet minuscule, canvassed in coal and debris.

“We really want to pipe water here,” he murmured. “She’s a child, she should be taken care of.” He lit up as he looked under neighboring stones – the glacier mass child was spreading under them. “She’s developing!” Baltistani reported.

Ice sheet mating is a dubious cycle.

Karim, of the Agha Khan Organization, says the cause directed glacier mass mating during the 1990s, yet it didn’t work. The organization quit subsidizing the venture. Shamsher Ali, the town senior of Machulo, says his elderly folks attempted, and fizzled, to grow an ice sheet child about 10 years prior.

Steiner, the hydrologist, noticed that in fact occupants aren’t growing an glacier mass. “The meaning of a glacial mass is it must be dynamic. It needs to move. In the event that it doesn’t move, it’s simply a block of ice.”

Zakir Hussain of the College of Baltistan, a specialist on Balti culture who prompts inhabitants on ice sheet mating for the U.N., called for persistence. Regardless of whether done accurately, “as indicated by native information, it requires 12 years to flourish and afterward an additional 12 years to develop,” Hussain says, a not great time period for individuals who need water now.

Taking for the sake of water

In Machulo, a town nearly four hours’ movement from the location of the ice sheet mating, occupants are spurning the law to get water. The ladies and young ladies who refer to themselves as “the water hoodlums of Machulo” accumulate by their town stream, their numbers expanding as the light blurs. Some snap gum and tattle. Others sit unobtrusively on rocks, scoops flung about the scene.

“I’ve come to take water,” snickers Zahra, a means rancher who surmises she is 50 years of age. “This large number of ladies have. We are a women’s pack,” she expresses, signaling to the ladies and young ladies gesturing terribly in understanding around her. “We need to make it happen. Generally our fields will go dry.”

As night falls, the ladies get their digging tools and stack up mud and rubble to impede the doorways of water channels that expand like outstretched arms from Machulo’s stream. Those trenches have a place with different inhabitants, prompting their properties. By hindering them, the ladies can redirect more stream water into their own trenches, to flood their minuscule fields of wheat, grain and poplar trees.

“In Machulo we are only battling each other for water,” Zahra says, glaring. Like the greater part of the ladies talked with, she declined to give her family name since it is thought of as dishonorable for a lady to be freely named in her moderate Muslim people group. Furthermore, likewise, on the grounds that she was taking water.

Torrential slide gathering and ice towers

In the interim, Hussain, the guide on U.N. projects, says he is guiding other, more quick measures, for example, torrential slide reaping, supported by a U.N. award. One evening, he strolled NPR journalists up a dry riverbed, following it increasingly high up a lofty slope to the foot of a transcending mountain, where it turned into a rough, tight canyon.

There, Hussain had constructed three progressive nets of thick iron wire across the chasm, darted into the stone on one or the other side. “What we trust is to forestall the torrential slide before it starts, by catching the stones here,” he says. In the event that the stones that trigger a torrential slide could be caught, they wouldn’t set off additional stones that would roar down the mountain to the towns.

The nets had another reason, Hussain says: The nets would catch and channel snow and ice, sending meltwater into the dry stream bed and supporting water supplies further downstream, he says.

Other Baltistan occupants are building ice stupas, spearheaded in the adjoining An indian Himalayan area of Ladakh by dissident Sonam Wangchuk. A stuparefers to a domed or cone shaped Buddhist sanctuary, and portrays the state of these frozen designs.

Basically, these designs are made by pipes that overview from high mountain streams to a lower-height region that can freeze in winter,usually a concealed chasm. The lines interface with spouts that, through gravity, splash water out of sight, making a fine fog. The fog freezes through the colder time of year and structures a frozen pinnacle that melts in spring, when ranchers need water.

In the town of Pari, Bashir Haidari, a self-educated handyman and circuit repairman, was roused to take a shot at making an ice stupa.

Haidari says their snow-took care of stream dwindled to where ladies couldn’t develop food to take care of their kids, and young fellows left to work in urban communities since they couldn’t bring in cash cultivating.

“I can’t perceive you how we had been enduring,” Haidari says.

Quite a while back, he tapped on a Facebook video shared by companions on the most proficient method to develop an ice stupa, “and I started envisioning how I could construct it,” he says. It’s almost difficult to go among Baltistan and Ladakh, attributable to struggle among India and Pakistan, so Baltistan inhabitants like Haidari are learning through internet based recordings and mystery.

Haidari went to his mosque for Friday collective petitions. With the mosque actually packed after love, Haidari reported he could possibly tackle Pari’s water shortage – and requested volunteers to assemble an ice tower. A small bunch said OK.

Generally, says Yasir Parvi, a rancher who joined Haidari, “individuals thought he was intellectually unsuitable. ‘A pinnacle of ice? He’s gone frantic!’ ” he reviewed townspeople murmuring.

Haidari’s workers made twelve ice stupas in a canyon two or three hundred feet above Pari town, which occupants accepted was a social occasion place for lahlus, naughty phantoms. Parizads additionally lived there – wonderful, supportive pixies, says Parvi – albeit neither one of the animals assisted with building the ice stupa. “I wish! They might have alleviated us,” Parvi hoots.

Haidari and Parvi took NPR correspondents to see the stupas. They had been softening through the spring, sifting into an underground stream that arose in the town. What was left was a truck-sized heap of ice.

Parvi took out his telephone to show a video of similar stupas in winter before they liquefied – a progression of ice-blue frozen wellsprings covering an Olympic-pool measured breadth. “It was wonderful,” he murmurs.

Steiner, the mountain hydrologist, says ice stupas, glacial mass mating and torrential slide reaping won’t “tackle the more extensive issue” that climate change is introducing. Yet, such measures could “ease the greatest difficulties that individuals have in their town” – in particular, a consistent stock of water for water system. According to what’s more, he, these procedures are low-tech, minimal expense and should be possible by local people. “That is an answer that is really going to work eventually, in light of the fact that they have command over it,” he says.

In Pari, Haidari recognizes the restrictions of ice stupas, which must be implicit high-elevation regions. According to in any case, it’s something special, he, signaling to his own town, where kids are done going hungry.

“We are proposing to fabricate an ice stupa to any town in Baltistan that has a water deficiency,” Haidari says. “For humankind, to battle against a worldwide temperature alteration.”

With additional reporting by Zeba Batool and Abdul Sattar in Machulo, Skardu, Chunda, Pari and Kunais